Children who consume the lowest-calorie sweetness do not cut the sugar, they increase the concerns that these “healthy” products can strengthen the habits of poor diet.

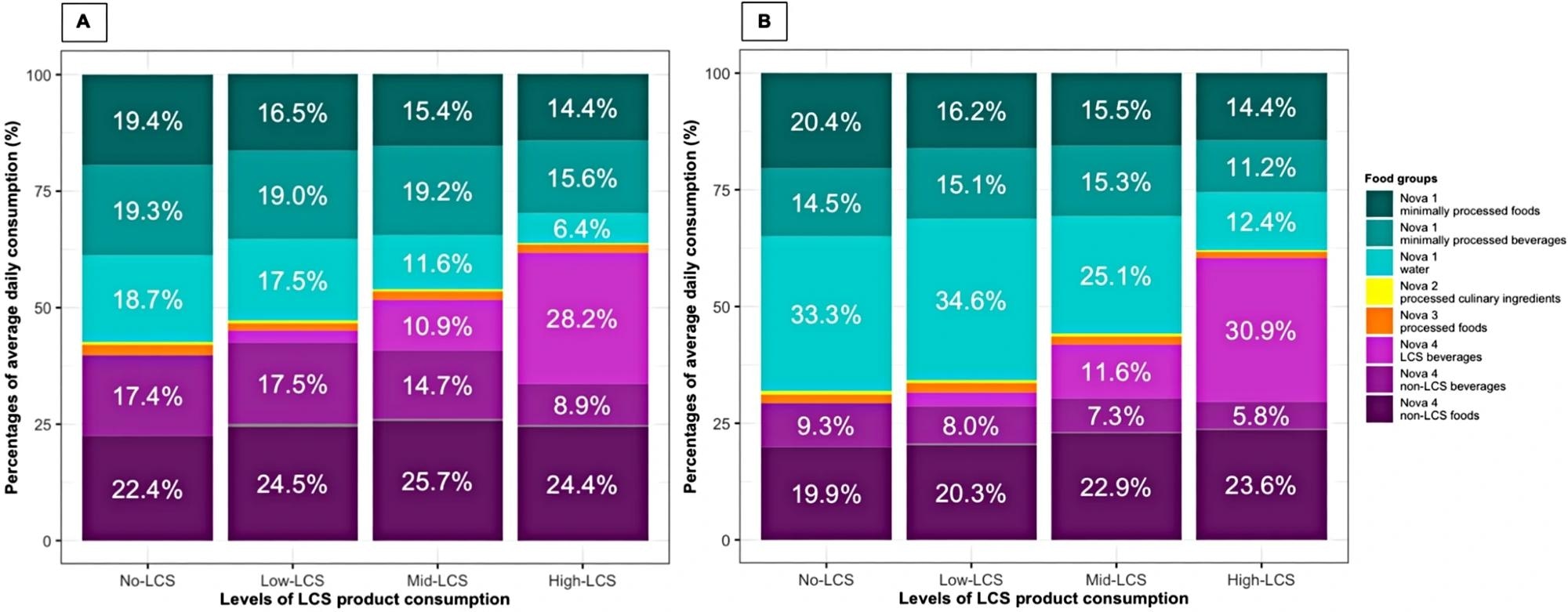

Village of dietary intake by Nova Subgroup in 2008-2009 (A) And 2018-2019 (B, A (N = 646). Percentage of dietary intake by Nova subgroups. No-LCS: Nova 2 Processed Pak content, 0.4%; Nova 3 Processed Foods and Beverages, 2.3%. Low-LCS: Nova 2 Processed Cooking, 0.5%; Nova 3 processed foods and drinks, 1.6%; Nova 4 LCS drinks, 2.6; Nova 4 LCS Foods, 0.5%. Mid-LCS: Nova 2 Processed Pak content, 0.4%; Nova 3 processed foods and drinks, 1.8%; Nova 4 LCS Foods, 0.4%. High-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary material, 0.3%; Nova 3 processed foods and drinks, 1.7%; Nova 4 LCS Foods, 0.3%. B (N = 424). Percentage of dietary intake by Nova subgroups. No-LCS: Nova 2 Processed Pak content, 0.6%; Nova 3 Processed Foods and Beverages, 2.0%. Low-LCS: Nova 2 Processed Cooking, 0.5%; Nova 3 processed foods and drinks, 2.1%; Nova 4 LCS drinks, 3.0; Nova 4 LCS food, 0.2%. Mid-LCS: Nova 2 Processed Cooking, 0.5%; Nova 3 Processed Foods, 1.7%; Nova 4 LCS Foods, 0.1%. High-LCS: Nova 2 processed culinary material, 0.3%; Nova 3 Processed Foods, 1.3%; Nova 4 LCS Foods, 0.1%

recently European Journal of Nutrition The study examines LCS product consumption and total energy, water, ultra-produced food and beverages (UPFB) intecce and free sugars between the age of 4 to 18 years of age between UK children.

Excessive free sugar intake and health risk

Consumption of highly free sugar is associated with increasing risk of cardiometabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular events. The previous study estimated that UK children consume about 12% of their total dietary energy intake with free sugars, which is almost double the recommendation of 5% of the UK Government and the World Health Organization (WHO).

In Britain, one of the three children aged 10 to 11 is of unhealthy weight. To address this, increasing consumption of sugar-sweet beverages has been an important point of intervention. To reduce obesity among children, many policies, including soft drink industry levy and sugar redeeration program, have been applied to reduce sugar content in foods and beverages. However, these strategies promoted LCS products that include Saccharin, Sucralose, Aspartame, Acesulfame Potassium, and Staviol glycosides as a low-sugar option.

Although random controlled tests have indicated short-term benefits of replacing sugar-sweet beverages with LCS options in obese adults about weight loss, longitudinal observation studies have presented contradictory results. LCS consumption is associated with cancer, obesity, adverse cardiomyatabolic results and risk of mortality in longitudinal studies.

The underlying mechanisms by which the consumption of LCS increases the risk of cardiometabolic disorders is poorly understood. Scientists have proposed that the exposure to early life to LCS can affect the reaction of sweet taste, dining patterns and the physical processes of hunger during development. LCS intestine can cause microbial dysbiosis and can induce inflammation of the low-grain, which increases the risk of impaired glucose metabolism and obesity.

It is necessary to understand how the consumption of the LCS product affects the overall diet pattern, which includes both ultra-transmitted and minimal processed foods. This information will help policy makers focus on strategies to improve the quality of diet and healthy weight in children.

About studies

The current study envisages that LCS is formed a lower-suited diet patterns below high levels of product consumption, which is characterized by high level of ultra-transmitted foods and lower levels of minimal processed foods. To test the hypothesis, between 2008 and 2019, data was collected from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) between a national representative dietary survey.

The current study classified 140 items as LCS products, which were consumed by NDNS participants. For each participant, the daily concentration of the LCS products consumed was relative to the total amount of food and beverages.

Participants were assigned to four groups based on their concentration of LCS product consumption, including no-LCS, low-LCS (6.8% g/less than 6.8% g/d), middle-LCS (6.9% and 17.4% g/d), and high-LCS groups (above 17.4% G/D).

Study conclusion

A total of 5,922 children were included in this study, with an average age of 10 years. About 49.2% of the study consisted of boys, 89.0% of white ethnicity, and 64.9% had a general body mass index (BMI). More than 36% of the participants were the lowest domestic income.

Compared to other groups, the children in the high-LCS group were small and more likely to have white ethnicity. In the years of survey, proportional distribution of children in each group, LCS consumption characteristics and average LCS intake are relatively unchanged in all study groups.

Between 2008 and 2009, 70.4% of the participants consumed LCS products, the average daily intake of which was 256.5 grams. No significant changes were observed in the spread of LCS products and average intake in the period of study. Interestingly, between 2008 and 2009, a shield of low water intake was seen with increasing levels of LCS consumption.

Compared to non-LCS product consumers, high LCS product users had to consume low water intake, non-LCS ultra-produced drinks and minimalized beverages. While high LCS consumers initially had low intake of free sugar, this difference was no longer statistically important by the end of the study period, showing a trend convergence over time.

The total energy intake for low-LCS and high-LCS groups saw a decline, with 14.8 kcal/day and 12.3 kcal/day out of aging compared to the NO-LCS group. Therefore, compared to non-LCS product users, LCS products saw a decline in total energy intake among the highest consumers.

Interestingly, all LCS consumption groups demonstrated a tendency to decline in UPFB consumption during the study period. However, this positive trend was less pronounced in the high-LCS group. Similarly, an increase in minimum processed food and water intake in 11 years was the slowest in the high-LCS group, indicating a frequent and wide relative interval in the quality of the diet.

conclusion

The current study has shown that the consumption of high LCS product was not constantly associated with the intake of low -free sugar in children, as the initial advantage disappeared over time. In addition, findings have shown that while all children had improved in some ways, the most improved improvements for children consuming LCS products were slow. This indicates that these products may be part of the broad, low -healthy dietary patterns and that their promotion represents a possible missing opportunity to encourage more water consumption. In the future, more comprehensive research is required to understand the current diet pattern and their effects on children.

Writers pay attention to many borders, including the use of cross-individual data, which prevents the individual dietary change from time to time. They have been underestimated by the probability of residual confusion and potential of LCS intake from unmatched lifestyle factors due to data collection methods of survey.

Journal reference:

- Sisen, M. At al. , 64, 230. Doi: 10.1007/s00394-025-03740-8, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/S00394-025-03740-8