BBC World Service

Mustafa Ozer/AFP Getty Image)

Mustafa Ozer/AFP Getty Image)When the illegal Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) announced last month that she would end her decades -long rebellion against Turkey, Leela hoped that she could soon join her son.

Three years ago, the former sandwich seller left the house to join the group – a campaign by Turkey, America, Britain and the European Union as a terrorist organization – near the Iraq border with Iran, near the border of Iraq, in a distant Kandil mountain of remote.

Final in March, in addition to two videos, Leela has not seen him ever since.

“When I first heard about the announcement I was very happy,” says Leela, whose name we have changed because she is afraid of reprimanding the group.

“But as time has passed, nothing has changed.”

PKK has been in a struggle in war with Turkey for 40 years that has killed more than 40,000 people, many of them are citizens, and one of the longest -last -lasting ones in the world.

Some families strongly condemned PKK, while others proudly talked about how family members were fighting for the group and they felt that the sacrifice had paved the way for peace talks.

PKK announces that he would stop fighting, Turkey, his Kurdish was seen as a historic moment for minority and neighboring countries, in which the struggle is over.

But since then, no formal peace process with Türkiye has begun and with the report of killing both sides, there is no official ceasefire.

Getty images

Getty imagesInitially, with the aim of fighting for an independent Kurdish kingdom in Turkey, PKK has focused on demanding more cultural and political autonomy for the Kurds, since the 1990s.

Leela, who lives in the semi-lover Kurdistan region of Iraq, is the border of Turkey, he says that he had not even heard of PKK until his son came home talking about the ideologies of the group, an Iraqi-kurd in his twenty-nine condition.

She accuses a group of “brainwash” her son, assuring her that they were defending ethnic Kurdish minorities in Turkey, Iraq, Syria and Iran. Kurdish is the fourth largest ethnic group in the Middle East, but not a nation state.

Leela says that over time her son became more independent, making her bed, washing her clothes and making dishes. Now she believes that PKK was preparing her for a difficult life which he was living in the mountains soon.

The day he left, he came home with three “colleagues” to tell his mother that he was going to the mountains to start six months of training.

She says that she repeatedly tried to stop her from joining PKK but she was firm to leave.

“He was so firm. Arguing with him is not an use.”

Since then, Leela says that she regularly visit Kandil mountain in the hope of catching a glimpse of her son, but never saw her.

“If they let me see her once a year, I would be happy,” she says.

The BBC traveled to the Kandil Parvat, which was given a rare access by PKK to do the film there.

The mountains, which are very low populations and are known for their natural beauty, help to mold thousands of PKK fighters from Turkish air strikes.

The journey took hours to run narrow, bumpy roads in an area where there are some signs of residence in addition to a handful of farmers and shepherds.

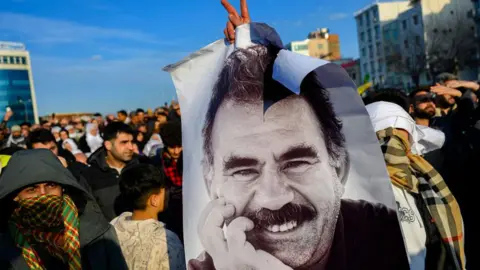

As the BBC contacted a PKK Czechpoint, we saw large pictures of group leader and founding member Abdullah Oklan as imprisoned by Turkey in solitary imprisonment since 1999 – displayed in the mountains. But when the BBC reached the checkpoint, PKK denied the US entry.

We were later told by PKK officials that a conversation with the group was going on and they did not want the media attention.

He did not reveal what was about the talks, although Iraq’s Foreign Minister Fuad Mohammad Hussain stated last month that the BBC discussion is happening with the PKK, Turkey, Iraq and Kurdistan regional government, to discuss how the group’s weapons would be assigned.

Disarmament ‘not for discussion’

So far, the terms of a possible peace deal between Türkiye and PKK are unknown.

PKK stated in a written statement to the BBC that this is honest and serious about the process, emphasizing its leader Oklan, being freed.

“The ball is now in Turkey’s court. A peace process may not develop based on unilateral steps,” said Zagros Hiva, spokesman of the PKK-Links Kurdistan Democratic Communities Union (KK).

But in a possible sign of further obstacles, a senior local commander, who is part of the second line of leadership within the group in Iraq, stated in a written statement to the BBC that his idea in his idea is “not for discussion”.

There is still doubt about Türkiye’s intentions, he says that “when we address the causes of armed conflict, the weapons will not be of no use for both sides”.

Turkish President Recep Taip Erdogan’s clear desire to end the struggle with PKK. Some people have interpreted as a dialect to attract Kurdish support for a new constitution to expand their 22 -year rule, which they denied.

He has described the decision of PKK’s decision to disintegrate as an important step for “our goal of Türkiye without terrorism”.

Writing on X, the Turkish President said that a new era was about to begin after “abolition of terror and violence”.

Getty images

Getty imagesFor some families whose loved ones were killed while fighting for PKK, this idea may soon end, it is bitter.

Kava Takur was 21 when he was killed two years ago. Her sister, Rondek Takur, who lives in the Iraqi Kurdish city of Sulemaniya, was last seen in Kandil Mountains in 2019.

Speaking from the family house, where Kava’s pictures beautify the living room walls, Rondek says his brother’s death changed the family’s life. “I always dream about her,” she says with tearful eyes.

Rondek, which is in its twenty -seventh condition, still recalls the final conversation that he did together.

“I asked her if she would like to go back home with me and she called me ‘sometimes’. She also asked me to join the mountains,” she says.

For Rondek and his family, who are supporters of PKK, the group decomposed group would be a moment of “pride and pain, especially after our huge loss”.

She believes that “this is the sacrifices made by us and the martyrs we have lost, paved the way for the leaders to talk peacefully”.

What happens next is uncertain.

There are questions about what will happen to thousands of Turkish PKK fighters and will they be allowed to re -organize in Turkish society.

Turkish officials have not yet said whether these fighters will be considered as criminals and will be faced with prosecution. But Turkish media reports suggested that fighter aircraft have not committed crimes in Turkey, which may return without prosecution, although PKK leaders may be forced into exile for other countries or need to live in Iraq.

It is also not clear what would be meant to dissolve the group for other Kurdish groups, especially in the north-east Syria, which Turkish considers as an off-shoot of PKK.

Getty images

Getty imagesDuring the Syrian Civil War, Turkish forces and Turkish -backed Syrian fighters launched a series of crimes to catch the border areas organized by the Syrian Kurdish militia, called the People’s Protection Units (YPG).

The YPG dominates a coalition of Kurdish and Arab militia, called the Syrian democratic force, which was expelled from a quarter to Syria with the help of an American -led multinational coalition.

YPG says it is a separate entity from PKK, but Turkey rejected it and considers it as a terrorist organization.

Erdogan has said that the decision to disintegrate PKK should cover “all extensions of organization in North Iraq, Syria and Europe”. SDF Commander Mazloom Abdi stated that PKK’s decision would “pave the way for a new political and peaceful process in the region”.

However, he has also stated that the disarmament of PKK does not apply to SDF, which signed a separate deal to merge with the Syrian armed forces in December.

In Iran, the PJAK group, which is also part of the KKK, has told BBC Turkey that it supports the “new process” in Turkey, but it is not planning to dissect or disintegrate itself.

PJAK is named as a terrorist organization by Türkiye and Iran. Since 2011, there is a real ceasefire between the group and the Iranian government.

Turkey says that PJAK PKK has an Iranian hand, but the Kurdish groups refuse it.

‘This city has brought me nothing but pain’

For mothers like Leela, all the complexities of politics and the complex balance of military powers throughout the region are irrelevant. What she cares is with her son again.

“He will return home when he gets tired of harsh life in the mountains, at some point he will realize that he cannot take it anymore.”

If this happens, Leela planned to leave her home to the city, where her son was admitted by PKK.

“This city has brought me nothing but pain.”