BBC News, Mumbai

Jugornot books

Jugornot booksSneh does not seem normal about Bhargava’s life.

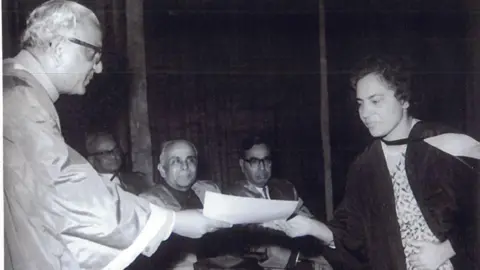

In 1984, she became the first woman to help the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in the capital Delhi – one of the top medical institutions in the country – and in her history of about 70 years, remains the only woman to do so.

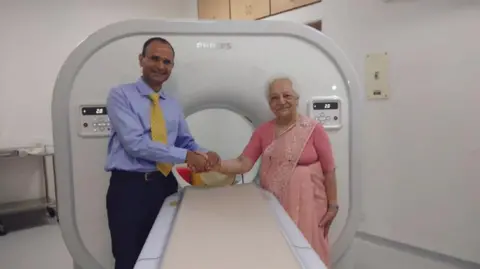

At the age of 90, Dr. Bhargwa – One of India’s leading radiologists started writing his memoir, The woman who runs the meims, Which was published earlier this month, and at the age of 95, remains an active member in the medical community.

Choosing radiology when it was emerging to be one of its most famous physicians in India in the 1940s, Dr. Bharagwa’s legacy is no less than extraordinary.

As a director of AIIMS, the job is not unlike its first day, which was no less than a test test.

It was on the morning of 31 October 1984, and the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, selected her for the role.

Jugornot books

Jugornot booksDr. Bhargava was not part of the meeting, but was reviewing medical matters for the day in his office. She remembers in her memoir that a colleague called her out, asks her to run away in the ward.

There, lying on a gurney was a very woman who said Dr. Bhargava was chosen to lead the hospital – Indira Gandhi. Her saffron saree was drenched in the blood and she had no pulse.

“At that time, I did not focus on it that he is the Prime Minister who was in front of me,” Dr. Bharagwa told the BBC. “My first idea was that we had to help him and save him from more loss,” he said.

Dr. Bhargava was worried that a crowd would bring a storm to the casualty ward, as a large crowd had already started gathering outside the hospital.

Reports started exiting: Gandhi was shot by two Sikh bodyguards in the revision for Operation Blue Star, in June to take out military raid militants on Amritsar’s Golden Temple.

Gandhi’s assassination has provoked one of India’s deadliest riots, which started hearing by Dr. Bharagwa as she was in a hurry to transfer the Prime Minister to one of the top floors of the building.

There, at the operating theater, a Sikh doctor ran away from the room, the minute he heard how Gandhi died.

The news of his death was to be kept in wrapped until his son Rajiv Gandhi was sworn in as Prime Minister.

“Till then, our job, for the next four hours, had to maintain the extreme that we were trying to save her life, when she was really dead when she was brought to AIMS,” Dr. Bhargwa writes.

Jugornot books

Jugornot booksHe also described the rigorous process of provoking the Prime Minister’s body, which would lie in the state in the capital for two days before cremation.

Dr. Bhargwa writes, “When we inject it into different main arteries, the emballing chemical,” Dr. Bhargwa writes. A ballistic report will later reveal that more than three dozen bullets punctured Gandhi’s body.

But Dr. in AIIMS This was not the only notable episode in Bhargava’s long and luxurious career.

In the book, she shares attractive anecdotes of her conversation with other prominent politicians, including the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru.

She also recalls that Sonia Gandhi remembers her son, a young Rahul after taking an arrow after an arrow for AIMS.

“Sonia Gandhi told me that she had to bring Rahul to us because Rajiv (her husband) was meeting the king of Jordan and was later given a fancy car as a gift, which her husband was eager to drive,” she writes in the book.

Rajiv Gandhi gave Rahul himself without security, as a surprise, without security, but Dr. Bhargava strongly stopped citing security concerns.

But it was not so exciting every day.

Dr. Bhargava recalled political pressure, including an MP who threatened him not to choose his son -in -law.

On another occasion, two top politicians, including the federal health secretary, tried to hand over to AIIMS Dean – although the decision was alone.

Dr. Bhargava says that she was standing against pressure, always prioritizing the patient’s care. He worked to establish radiology as a main part of diagnosis and treatment in AIIMS.

When Dr. Bhargava joined in the 1960s, while AIIMS had only basic imaging equipment. He trained colleagues to read the subtle signals in black and white X-rays, always in the context of the patient’s history. Later he pushed for better equipment, helping to build one of the major radiology departments of India.

Jugornot books

Jugornot booksDr. Bhargava was always ready to make a difference.

Born in a rich family in Lahore in undivided India in 1930, she preferred to play with a doctor for her doll and brother -in -law as a child. During the partition of India and Pakistan, Dr. Bhargava’s family fled to India and later, she will visit refugee camps with her father to help the people.

At a time when some Indian women chased higher education, Dr. Bhargava studied radiology in London – who is the only woman in both her class and hospital department.

She returned to India in the 1950s after hearing her guru that the country needed a skilled radiologist.

Dr. Bhargava often credits his family, and her husband’s generosity to help achieve her dreams, and she hopes that other Indian women will get the same support.

“It starts from childhood,” she says.

“Parents should support their daughters. In the same way they support their sons. Then they will be able to break the glass roof and arrive for the stars.”